Updated February 18, 2026

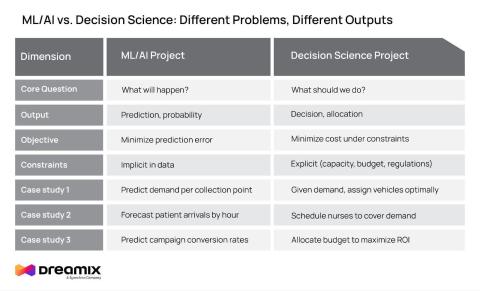

Machine learning answers "what will happen?" Decision science answers "what should we do?" In today's AI-driven market, connecting the two is a low-hanging fruit many companies haven’t tasted - and it can bring unprecedented efficiency.

Last year, a construction company showed their ML models for forecasting project costs. The predictions were solid – they knew with reasonable accuracy what resources they'd need across regions for the coming quarters.

But when it came to actually deploying teams – deciding which crews should go where, when, and for how long – they relied on spreadsheets and gut feeling.

Looking for a Artificial Intelligence agency?

Compare our list of top Artificial Intelligence companies near you

They'd invested in prediction. They had no system for decision-making.

This pattern repeats across industries. Organizations build sophisticated forecasting capabilities while missing the discipline that turns predictions into optimal decisions: Decision Science.

Decision Science emerged during World War II as Operations Research, developed to solve large-scale logistics and resource planning problems. Today, it uses mathematical optimization to identify the best course of action from all feasible alternatives.

Given your constraints and objectives, what decision maximizes value or minimizes cost? How should you allocate crews across multiple projects to minimize delays and overtime? Which equipment should be assigned to which sites to reduce idle time and rental costs? How do you sequence projects to meet deadlines while staying within budget and labor limits?

According to McKinsey's 2025 State of AI survey, while 88% of organizations use AI in at least one business function, nearly two-thirds have not yet begun scaling AI across the enterprise—highlighting how many companies stop at isolated use cases rather than embedding advanced decision capabilities into core operations.

Consider a waste-collection company optimizing its routes. Machine learning can predict which collection points will fill up this week based on historical patterns and local events.

But forecasting demand doesn't tell you how to assign vehicles to collection points, or in what sequence to visit them. Those are optimization problems with explicit constraints: vehicle capacity, driver hours, pickup time windows, traffic patterns.

Machine learning answers "what will happen?”. Success means accurate predictions. You build models, train on historical data, validate accuracy, and deploy forecasts.

In contrast, decision science answers "what should we do?". Success means minimizing cost or maximizing value under real constraints like capacity, budget, and regulations. You define objectives, model constraints, solve for optimal allocation, and execute decisions.

In other words, a forecast tells you demand will be high. Optimization tells you which vehicles to dispatch, to which locations, in which order, to meet that demand at minimum cost. Both are necessary, but neither is sufficient alone.

In airlines, logistics, and manufacturing, optimization has been standard practice for decades. Companies such as UPS have reported saving hundreds of millions of dollars annually through route optimization.

In aviation maintenance and operations, organizations including Lufthansa Technik and Delta Air Lines have used advanced planning and optimization techniques to significantly reduce aircraft-on-ground (AOG) costs and improve fleet availability.

But adoption varies significantly by company size. Large enterprises have dedicated Operations Research teams. Mid-sized companies hire consultancies for specific projects. Small operations stick with spreadsheets and manual planning.

Outside these traditional industries, however, the gap widens considerably. Most retailers, healthcare organizations, professional services firms, and technology companies don't recognize that they have optimization opportunities. They view these challenges as requiring business judgment rather than mathematical solutions.

Yet any company making repeated decisions about inventory allocation, workforce scheduling, marketing budget allocation, or pricing under capacity constraints faces optimization problems. These decisions follow patterns, operate under explicit constraints, and have measurable objectives.

And that makes them perfect candidates for optimization.

Classical optimization assumes everything is known upfront: demand, fleet size, and schedules. Machine learning changes that.

Consider waste collection again, for example. The classical Vehicle Routing Problem assumes you know which bins need emptying. Reality, however, is much messier. Fill rates vary by location, season, and weather. Machine learning then comes to the rescue, predicting when each collection point actually needs service.

This makes the system dynamic. Routes adjust based on predicted need rather than fixed schedules. You empty bins before they overflow, not because it's Tuesday.

As a result, the value compounds. If demand shifts geographically, machine learning catches the trend early. This helps make bigger decisions: Should we buy more trucks? Should we relocate depot capacity?

The pattern repeats across industries. In aviation, ML predicts when aircraft components will fail, and then optimization determines the best maintenance schedule to minimize downtime. In healthcare, ML forecasts patient admissions, then optimization creates staff schedules that match predicted demand.

Machine learning tells you what will happen. Optimization tells you what to do about it. Without both, you either have information you can't act on or decisions based on wrong assumptions.

Optimizing today's decisions perfectly, however, doesn't mean you're optimizing the business. You can win every battle and still lose the war.

Consider a delivery company that perfectly routes its trucks each day with its current fleet. Meanwhile, customer demand is shifting to a new region where the company has no local depot. Or think of a company maintaining old trucks because the daily maintenance costs seem manageable, when replacing the fleet would actually cost less over time.

Strategic optimization means looking at the bigger picture. What setup minimizes total cost over months or years, not just today?

A current project, for example, optimizes daily shift assignments for airport ground staff – who works which shift, respecting overlaps, qualifications, and vacation constraints. However, the staffing levels and shift structures are taken as given. Looking at demand patterns over quarters or years could reveal whether to hire more staff in certain categories, restructure shift timing, or redistribute headcount across qualifications. The daily optimization runs perfectly within constraints that might themselves be suboptimal.

Several factors play a role here. Most business leaders are familiar with AI and machine learning, but fewer have experience with decision science or optimization, which are typically taught in more technical fields. When organizations talk about “AI strategy,” the focus is often on tools that analyze data or generate insights, rather than on systems that directly recommend decisions.

Recent research from Deloitte shows how quickly AI adoption is moving: nearly half of surveyed organizations say they are moving fast with Generative AI, and many are prioritizing efficiency and productivity gains. At the same time, Deloitte’s survey highlights that scaling AI remains challenging due to talent gaps, organizational change, and difficulties in measuring value. Nearly three-quarters of organizations expect to rethink their talent strategies as AI adoption grows.

These challenges are even greater when organizations move from prediction to decision-making. Over the past decade, predictive modeling has become far more accessible through cloud platforms, pre-trained models, and managed services. As a result, many teams can generate forecasts quickly and at scale.

Decision-focused approaches, however, require a different mindset. They force organizations to define objectives explicitly, model real-world constraints, and accept trade-offs between competing goals. This work depends more on problem formulation and domain expertise than on model accuracy alone – and it often cuts across organizational boundaries.

The result is a visibility gap. Forecast accuracy is easy to track and communicate. The value of better decisions is harder to isolate, because it depends on comparing outcomes against alternatives that were never executed. Faced with this complexity, many organizations stop at insight generation, even when the real value lies in systematically translating those insights into action.

A few simple questions can help you spot optimization opportunities in your organization:

If you regularly assign limited resources to competing needs, there’s likely room for optimization. This goes beyond delivery routes. Sales territories, project staffing, inventory placement, and budget allocation all follow this pattern.

Think capacity limits, budgets, regulations, or service commitments. If you can list them clearly, they can usually be modeled. The clearer the rules, the better optimization works.

Statements like “this is how we’ve always done it” often signal missed opportunity. Human judgment works well for small problems, but it struggles as decisions scale. What works for a handful of choices breaks down when there are hundreds or thousands.

If you’re predicting demand, usage, or customer behavior, you’ve already done the hard part. Optimization is the next step. You know what’s likely to happen—now you can decide what to do about it.

Companies that outperform connect prediction and optimization, using forecasts as inputs to decision models that turn insight into action.

This discipline has been around for decades and proven in high-stakes environments. Today, it’s more accessible than ever. Many organizations still manage complex decisions manually – not because better tools don’t exist, but because they haven’t recognized these problems as ones that can be modeled and improved.